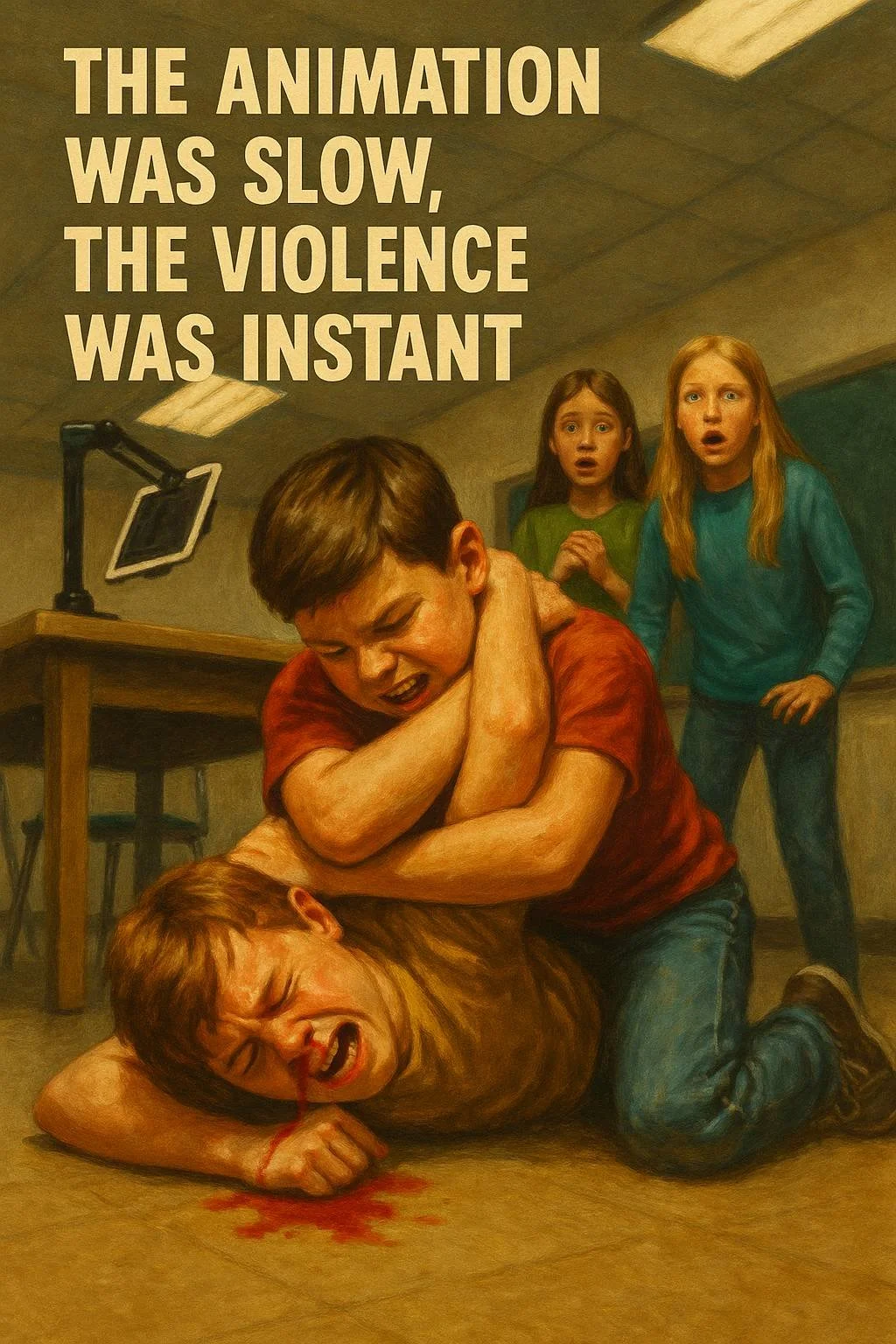

This is a true story. Kids aren’t just making a film—they’re defending a border. In their world, content creation isn’t a hobby; it’s aspirational.That’s why they come in hot.

Joe steps into the media lab and takes in the scene. Thirty kids, stations set like a miniature studio—Chromebooks with webcams, iPads on utility arms, all grouped around tables like bustling little production crews.

“Right,” he says, clapping his hands lightly. “Everyone gets a turn—director, animator, camera operator. Rotate after each scene. The director’s your quality control—no one takes a picture until the director has given the all-clear. You’ll be looking for the usual suspects: stray fingers, shadows from elbows wandering into the shot. Got it?”

Heads bob.

“I’ll be wandering around like a man with nowhere to be,” he adds, “but the truth is I’m keeping an eye on everything.”

He moves between groups, noting the variety. One group is doing a long establishing shot—nothing moving yet. Another is working on a close-up series of animated mouth shapes for a future lip-sync loop.

And then—ah, the Turtle Group.

He stops. “Now that,” he says to no one in particular, “is intriguing.”

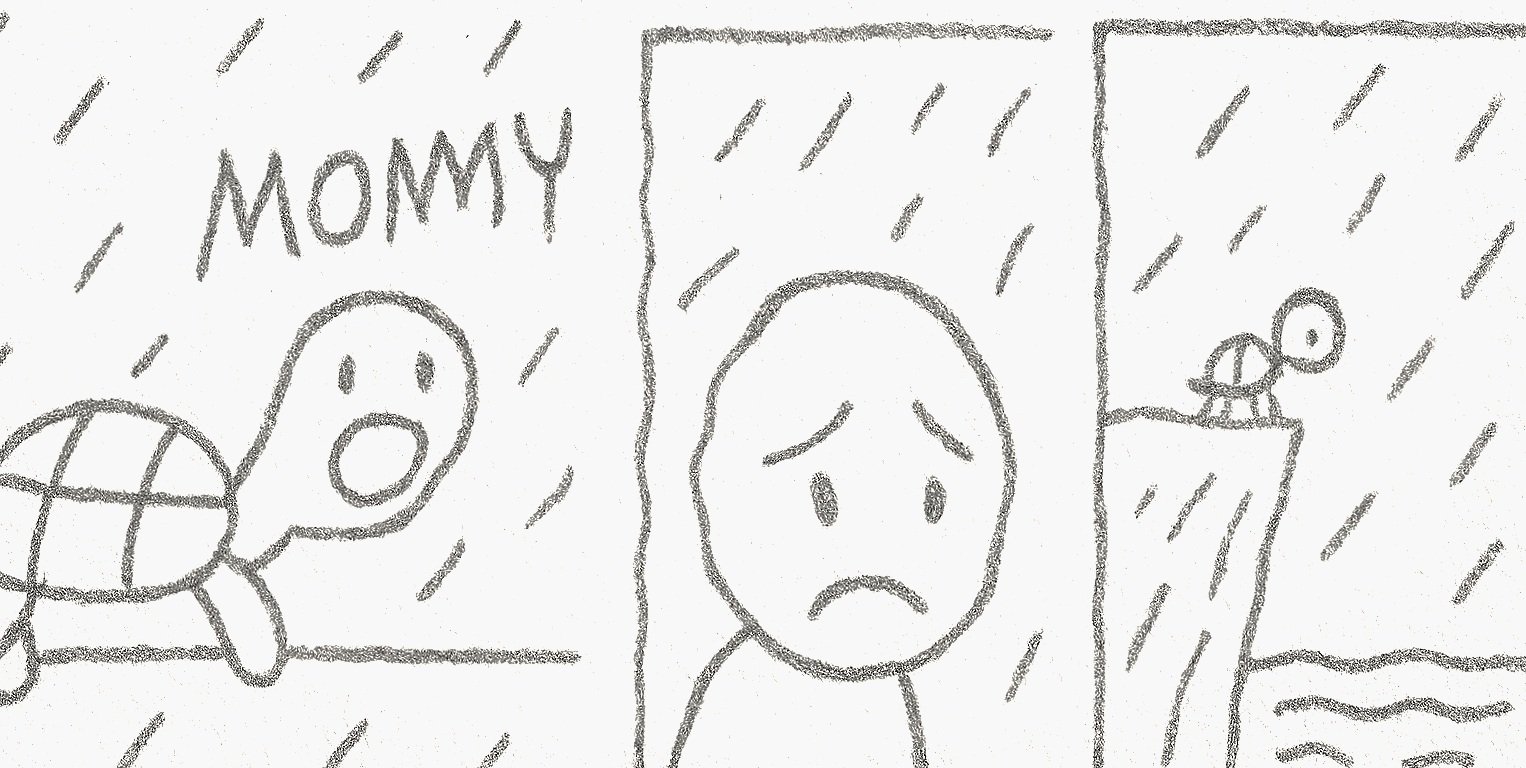

They’ve set up a walking turtle in the snow using the rule of thirds. "Great cinematography," Joe exclaims,."And the snow hack is brilliant—three clear plastic sheets, each covered in white crayon dashes. Swap a different sheet in each frame, and you’ve got a snowstorm that dances." "Who thought that up?

"James" the group blurts.

"Way to go James, let's see if it works. Who’s directing here?” Joe asks.

“I am,” Maria says, steady and confident.

She rattles off the crew. James and Juan animate, Daisha takes the pictures. Maria directs.

“Two animators?” Joe asks.

Maria explains—Juan moves the turtle, James handles his snow sheet hacks with pride.

Joe leans in. “Is our turtle trudging left to right, or staying in the middle like the camera’s tracking along, following him?”

“In the center,” Juan says. “Easier. We just do 5 or 6 steps of the turtle walking in place, then loop it.”

Joe smiles. “Now, that’s thinking ahead. Saves a lot of turtle walking animation. You're applying all those looping secret recipes from the Animation Chef's White Hat section! Most kids would have the poor thing trek across the whole screen—much more time consuming."

They begin. Juan places the turtle—head and shell one piece, four separate paper legs at the ready. James lays the first snow sheet on top.

Alternating clear snow sheets, a genius hack.

“Click!” Maria calls. Daisha clicks.

“Wait,” Maria says. “Shadow.”

Joe watches James glance up at the overhead lights, sees the shadow slicing through the scene, and nods "Oops!". They reset. This time, no shadow. Click.

Joe crouches beside them. “How many frames for the legs?”

“Five or six,” Maria says.

“No,” James cuts in. “Fifteen frames per second. Five frames is only like a third of a second. Fifteen divided by five is three! Duh!”

“We’re looping,” Juan reminds him. "We can copy and paste as many times as we want. Duh!"

Daisha suggests a test run—shoot a few more, then see how it feels.

Joe feels the air shift. James’s is a bit overbearing and dismissive and pushing on the group’s patience. A number of eyes roll. This was James being "James" evidently.

They compromise, shoot extras. Playback confirms James’s point—it’s too quick. Maria sides with him, and they commit to the full 15-frame cycle.

Then—small friction. Juan notices James reusing a snow sheet.

“You already used that one,” Juan says.

“No I didn’t,” James replies as if someone was publicly shaming him.

“You weren’t looking—you put it down, picked it right back up. Pay attention, dude.” Juan jabs.

James and Juan have a history.

It happened fast—James lunges at Juan as Juan stands to deflect the charging force, and down to the floor they go. James locks Juan in a full nelson head lock, and into full combat mode they go, chairs skidding and clattering and bashing into each other as screams come from around the room.

Joe freezes for half a beat. Well, that escalated quickly. The teacher and TA are quick, on the scene before Joe is barley processing what is happening, breaking them apart. Juan’s nose is bleeding. James is spouting off every word in the book. A student rushes over with a wet paper towel for Juan.

The teacher and the TA lead both boys out. After a moment of stunned silence and nervous laughter, the room exhales.

Like the other groups, the turtle group goes heads-down, an work resumes—faster now, not only to make up for lost time, but because every vein in the room is juiced with adrenaline.

Joe steps aside and disengages until the teacher returns. The TA comes in, helpf surprise all are applied and moving forward.

What seems like an eternity passes.

Juan returns with the teacher, gauze in his nose, eyes red but jaw set. He insists on finishing. His group has finished the turtle walk cycle and are very excited to show Juan, all 15 frames. And—heaven help them—it looks good. Which means, yes, James was right about the frames required for this scene.

Maria raises her hand. “When can we get James to see this?”

Later, James is escorted back into the room by a TA. Maria hits play. The turtle walks through a snowstorm that shimmers and shifts.

“Whoa, that’s riz,” James says, grinning.

He spots the double snow sheet—his double frame snow sheet mistake. Daisha scrubs through the series of frames and erases it. They play it again. Perfect. Scene two: finished.

James, vindicated, is escorted back out to whatever fate awaits him at the principal's offce (he will return next time).

The group reformats: Maria on camera, Daisha animating, and Juan directing. Next scene underway.

Joe leans back, thinking, "It’s more than a classroom project; it’s territory they rarely get to claim. Even after blood on a shirt, pride dented—they find their way back to the table, hands on the work, eyes on the next shot. The show must go on!

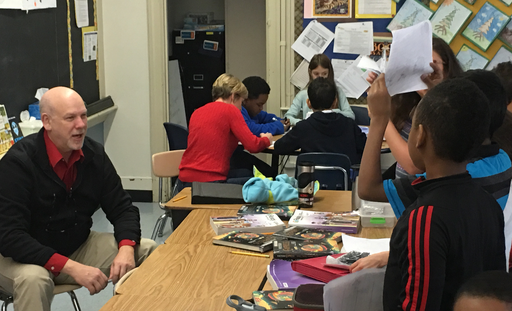

Joe demonstrating film making to 4th graders in NYC

Founder of Animating Kids and executive producer of the Animation Chefs webseries, Joe turns filmmaking into a team sport for the content creator generation. Starring his own kids as the “Animation Chefs” with his wife, Holly, as production designer and script supervisor, Animating Kids uses a by kids, for kids cooking-show format to inspire young creators worldwide. Out in the real world, live hands-on workshops with 25,000+ students and educators trained in 20+ countries, Joe equips kids with the storytelling framework and creative vocabulary they’ll need to thrive in the digital age—whether directing a film or prompting an AI. His work proves that visual media literacy is reading and writing with sound and motion—complementing traditional literacy and making media production relevant for the todays kids.

Animating Kids Table of Contents

More Testimonials:

"I am impressed by...these programs, providing young people with the skills to become creative and critical thinkers...this shares my dedication to nurturing the next generation of filmmakers and visual storytellers."— Steven Spielberg - Referencing the work of Joe Summerhays“

"Joe (Animating Kids Founder) has turned the art of movie making for kids into a science.” — Jonathan Demme - Academy Award-Winning Director

“I absolutely love Animating Kids...you have no idea how amazing it is for a span of K-9. I’ve got the whole building covered and my planning was done for me. The kids LOVE the Animation Chefs. Win, win!!”— J. Tuttle - Media Specialist

"When I found Animating Kids it changed everything. Small and not so small humans became masters of sound and motion on any subject via small group PBL dynamics."— Rachel - Tech Coach - Quebec

“Animating Kids has changed everything! Fun, relevant media-making lessons for kids, and total P.D. for my non-film making teachers. A complete solution!!” — Principal - Bronx NY

"Animating Kids really helps focus our students during remote sessions…it keeps them so engaged. Your secret recipes are a life saver." — Marisol - Sacramento Ca

"The kids love the demonstrations and it is P.D. for me as I tee it all up. Animating Kids makes me the coolest educator in their lives!" — Charlotte - London UK

"This is the most important skills-based content for today’s kids. I don't think primary educators get how impactful this approach can be. It respects media content creation as the basic literacy it is for today’s kids. — Monique - White Plains NY

“We went through the entire process (PD workshop) of learning animated filmmaking with our tablets and smartphones. We could barely keep up. In the end we came away exhilarated rather than exhausted.” — Cathy S. - Librarian“

"My head was spinning. It involved: math, writing, science, team building, art, language arts, engineering, improvisation, innovation, acting, etc. Along with another dozen areas I can’t recall. Sneaky comprehensive. Mind blown. Can’t wait to use it in class.” — Marcia - 4th Grade Teacher

“Animation Chefs have created a really inspired program! My test group of (hardened gang members) like to laugh at the videos, and they love the simple clear explanations. They just have a blast...”

— G. Zucker Austin TX

"Thank you SO much for sharing your wealth of information and opening this world to every kid! I first learned about you when my husband introduced our daughter to you. Now I am bringing it into my after school program. I’m so psyched!" — Joy H. Retail After School Specialist

"Kids sign-up for robotics, coding, and stop motion sessions. After taking all three, they rate stop motion as their favorite track BY FAR. Animating Kids is key to our success." — Shane V. After School District Lead